CONTENTS

Even if she was a widow, she was somehow a virgin. Or so lightly touched by a previous marriage she was considered pure enough for the purposes of being an appropriate wife in the 1950s post-war mystique, which was eager to yank women out of workplaces and into pedestal-shaped cages.

Pulp vs. Purity

Pulp Romances

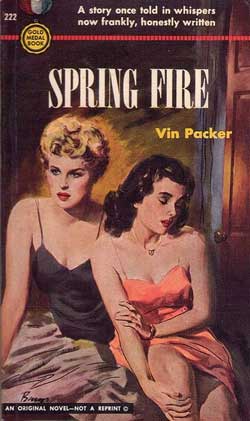

At the time, there was a distinct separation between pulp romances and what I’m calling “purity” romances. Pulp romances were distributed through bus stations and drug stores. Their love stories didn’t arrive at a happy ending without lurid events, like lesbian side affairs or dalliances with bad boys that lead to brushes with the law. While they could be exploitative, pulp romances had real world problems like sexual assault, battering and bullying, substance and alcohol abuse, and the lack of financial autonomy that drove women to desperate measures.

Pulp novels of this era were the first to posit lesbian stories that didn’t end in death for the “predator lesbian.” They were books so inexpensive and brief they could be read on a bus journey and left behind, no one the wiser that you’d been gobbling up tales of premarital sex, walks on the wild side, and the temptations of Those Kinds of Women. It’s a pulp romance, Spring Fire, that opens Irene’s mind in Wind in Her Hair to the idea that women can not only be true and valued friends to each other, they can also be lovers.

Purity Romances

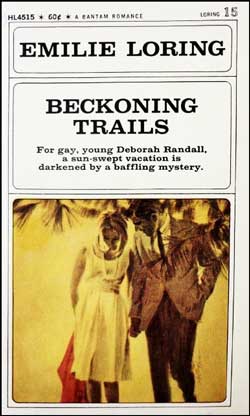

Beginning in the immediate post-war era, mainstream romance steadily set itself apart from pulp romance by emphasizing stories about good girls who marry serious men in boxy, tweedy suits. Considered lesser but lucrative from the likes of Mills and Boon and Harlequin, even large publishing houses produced their own lines of respectable romance reading. Heroines might have adventures, travel the world, act or sing, but her world was free of vulgarity, and she was most definitely a virgin and eligible for a white wedding. That’s why I call them “purity” romances.

Did they give women the wrong idea about their role in society? Yes. But then so did literary fiction and all the other kinds of fiction, including stories that had no women at all.

Romances from these publishers were distributed via direct mail subscriptions and to bookstores and libraries. Many were produced in hardcover. In this era, covers were chaste with everyone fully clothed. Purity and virginity walked hand-in-hand with handsome, prosperous older men.

It was central to nearly all the purity romances I read that the heroine was earning a living – a secretary, nurse, teacher, nanny, or running a genteel family business. She might be an aspiring performer or artist. She was not actively trying to find a husband, hadn’t dated much (virgin, remember?), but she wasn’t exactly a career woman either. She worked because she needed to, usually for the sake of others. It was tacit that she would leave any job or artistic hobby to become a housewife because, in this idealized world where virtue is rewarded with an excellent marriage, being a housewife was the only life a pure and virginal woman could want.

Women Are Enemies

One other central aspect of many purity romances was the lack of female friendships. There were intergenerational ties with aunts and grandparents aplenty, but a deeply valued woman friend – which is a staple now of a lot of romance – was a rarity, and if she existed it was not to pass the Bechdel test. The inevitable heart-to-heart enforced norms a la “He’ll make a great husband, my dear” or “He’s rude and uncommunicative, but that’s because he likes you.”

Otherwise, other women in the stories were competitors and manipulators – the literary descendants of Caroline Bingley from Pride and Prejudice without a Charlotte Lucas in sight.

Irene – Caught in Between

As I said above, I read a boatload of purity style romances long before I ever knew that lesbian pulp fiction existed. When I began creating the character of Irene earlier this year, I asked myself this central question: How can Irene’s story pull both of these highly popular and socially influential styles of romance into a cohesive narrative about a woman’s life in 1952?

Irene is hemmed in on all sides by expectations of purity, but her reality is much closer to that of women in pulp romances. As a widow, she presents the proper face to the world. She carries painful truths in silence, with strength, but that silence also brings shame. Shame is what gives secrets power. When she can finally speak these secrets it integrates her into a sense of self for the first time in her life.

My ideal in historical romance is to honor the real struggles of women in an era, and to find her a good woman to love in a relationship and setting that can realistically survive – because we were there, and we did survive.

In 1952 there was no living openly as lesbians. Women who traveled and lived together lied to save their lives. Many lesbians created mystiques that showed people what they expected to see, the way that a purity romance powerfully assures us that the world is fine, all is well, no need to question or worry. Commonly, “sharing expenses” and “both had tragic love affairs and never got over it” were part of the normality they projected to keep jobs, pursue careers, have credit and property in their own name, and revel in safe, private happiness.

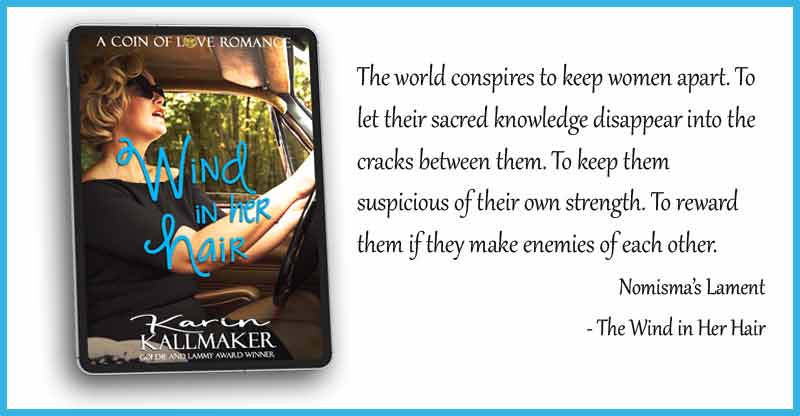

Snippet from Chapter 6 of The Wind in Her Hair by Karin Kallmaker. Copyrighted material.

It took a magical coin, two very helpful women, a wrong turn, and a fictional town to pull reality and longed-for happiness together for Irene’s quiet revolution. And, like purity romances, the story ends with the first kiss as it fades to black. I’m well aware that it won’t be to everyone’s taste, and that’s okay.

A Modern Concession

Unlike pulps or purity romances Wind in Her Hair has an epilogue that shows how two women in a community of friends could survive what was to come for women who refused the company of men, from McCarthy to security purges, to mental institutions. As history shows us, it got a lot worse before it got better.

In short, they survived the dark times together. As Louisa in Touchwood so eloquently details, friends had each other’s backs when it came to the dangers of society. And that’s a powerful lesson we can take from the pulp romances: life can suck, and persistent harm to us exists just because we’re women, let alone women living without men. We survive it.

The Lessons for Us Today

The world we face now, banning our books and scapegoating our trans family in the hopes that we’ll turn on them – all by liars and hucksters who paint our very existence as dangerous to children to make money and garner power – we’ll survive all of that too, together.

In the 1950s and today, it means a life where we seize the happiness promised in purity romances while surviving the world we’ve been handed with the tenacity, wiles, and daring shown by women in pulp romances.

As Nomisma says in her opening preamble in Wind in Her Hair, “These women, they fight.” Like our foremothers, we have no other choice.

Read the first chapter of Wind in Her Hair