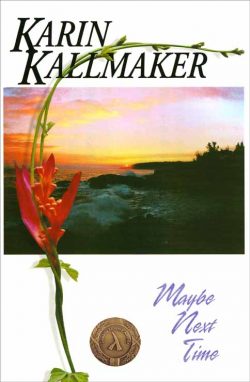

Sabrina Starling doesn’t need love. She has fame as a brilliant violinist and unlimited options for female company. Nothing can shake her — except the memory of her very first love. Knowing that neither the teenaged nor adult Jorie Pukui will ever return her feelings, Sabrina has escaped into her music and the arms of other women.

When injury leaves her temporarily unable to perform, Sabrina finally finds the one woman who could free her forever from the memory of those stolen Hawaiian nights with Jorie. There’s one problem. The object of Sabrina’s desire, Diana, is deeply in love with Pam, the woman who has shared her life for the past eighteen years.

A family funeral calls Sabrina home to the islands, but she no longer believes that the gentle breezes and possible welcome in Jorie’s eyes can repair the lives she’s shattered, including her own.

Karin Kallmaker’s searing novel of innocent first love and dangerous seduction joins an unparalleled string of critically acclaimed bestsellers that earned her the title of Undisputed Mistress of Lesbian Romance.

Edited by Greg Herren. Published by Bella Books.

My fascination and love for Hawaiian and Polynesian culture and spirituality is, I hope, reflected respectfully throughout the story.

- Maybe Next Time at the Lesbian ReviewA brilliant book. I loved every moment of it.

- Maybe Next Time at Midwest Review of BooksCompelling story of redemption, healing and surviving.

- Maybe Next Time – Lammy Winner!Maybe Next Time Winner of the 2003 Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Romance.

- Reader Comments about Maybe Next TimeA romance that reads like saga, is structured like a mystery, and is written with an ear for music.

- Maybe Next Time at Just About WriteA memorable tale… With flawed but likable main characters, an intriguing plot with many surprises, award-winning prose and flawless editing.

From

the Author

Signed Paperback

Secure checkout

powered by STRIPE

From

Bella Books

eBook and Paperback

Lesbian Owned Since 2002

All Other Retailers

Amazon, Kobo, Nook, Apple, and More

Search at your favorite retailer

Signed paperbacks from the author.

The eBook is currently available at Amazon through Kindle and Kindle Unlimited.

Audiobook via Audible now available!

If you purchased this eBook or audiobook from Karin's store and need to redownload, visit your account.

Part One: Kuamo’o

(The Frequented Path)

Chapter One

“Ms. Starling, you’ve got six claim checks, but I’ve only got five bags. What’s missing?”

Bree stared fixedly at the skycap but could still see the bag in question out of the corner of her eye, circling on the baggage claim conveyor. The violin case was soon going to be the only unclaimed item.

Walk away, she told herself. It’s that easy.

She’d never checked her instrument through the regular baggage service before, but this time she had hoped for fate’s intervention. Luggage went missing all the time. Items could be crushed beyond recognition. But the violin had survived. Even the fates wouldn’t take pity on her, not that there was any reason that they should.

She could have left it behind, she told herself. It would be as easy as, say, leaving her skin behind.

“Oh.” The round face split into a wide smile. “The violin, of course. I’ll take good care of it.”

He held it out, but she gestured at the cart. She would not touch it herself. If she didn’t touch it she could pretend the pain wasn’t there.

The skycap escorted her to the rental kiosk, then waited while a utilitarian white sedan was brought around. It wasn’t until after she had tipped him and settled into the car that she realized he had set the violin case on the passenger seat. He’d even fixed the seatbelt around it.

The car was an inferno in spite of the air conditioner on full blast. She shrugged off the jacket that had kept the airplane’s chill at bay and sat for a moment in the swelter. Her back broke into a sweat against the hot seat. It was one of the most alive sensations she’d felt in a very long time. It was not particularly welcome.

Her sunglasses were nowhere to be found. The glare was so bright she had to close her eyes halfway, leaving her no strength or inclination to look at the violin. She didn’t have to look at it. She had other things to worry about.

She turned south onto the Queen Kaahumanu Highway and idly punched on the radio. She quickly switched away from music, searching out news. Voices drowned out the crooning of the violin. She didn’t really listen, but the cadence was a kind of white noise.

Rock, island, punk, country, rock, classical.

No, she thought. Not classical.

She swerved into a dead end near a new subdivision and marina at Wawahiwaa Point. It was the fourteenth minute of the Tallis Fantasia. The bass line rose, in came the viola. She could see Osawa’s upraised hand, signaling her…

She was out of the car, standing in the dirt, with no recollection of having opened the door. The voice of her own violin poured over her body like lava. When she forgot her injury she called it Stupid Pain. When others forgot she called it Thoughtless Pain. She had nearly as many words for pain as her ancestors did for the wind, but there was no word for this agony, to hear the way it had been…

When the final note faded under the roar of a rising aircraft, she felt the tears on her cheeks and tasted iron in her mouth. The radio spilled out voices now, in measured tones.

“And welcome back to those of you listening today to the KUOH tribute on this fortieth birthday of the internationally known local girl made good, Sabrina Starling. That was the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, composed by Ralph Vaughn Williams, and recorded with the Stuttgarter Kammerorchester under the direction of…”

Bree backed away from the car, and only stopped when she stumbled. She’d reached the lava field. The voice was very far away. Soon there would be music, more unbearable music.

Dr. Sheridan told her to lose herself in the physical world when her head felt as if it would burst open from the waves of remembered music. All the gods, she wasn’t prepared for this trip, what would be required of her, how she would have to act. Not here, not with all the pain that had made the journey with her.

“Happy birthday,” she muttered. Forty was even less fun than thirty-nine had been. That the day was the thirty-third anniversary of her arrival on the island was completely unimportant, at least right now.

Look around. White car, black lava, blue sky, brown dirt. Any detail will do, Dr. Sheridan had said. She inhaled deeply and opened her eyes wide, trying to dampen the inner anguish with her external senses. The late afternoon air was heavy, damp, and stank of jet fuel. But underneath was the sea, the mountains, and the undeniable, almost electrical smell of sunlight on the lava field.

The air traffic above her quieted and the sound of her name unwillingly drew her attention back to the car.

“…Starling’s considerable and diverse body of work speaks for her past accomplishments. Though she hasn’t performed in public since a mainland concert two years ago…“

She forced air into her lungs, consciously making herself breathe. The sparkles behind her eyes gradually faded away. Look at anything but the violin, she told herself.

Beyond the black rubble was the orange-gold sun, arcing downward toward the alania sea, smooth, without swells or breaks. The breeze blowing in was as soft as the touch of a petal to her burning cheeks. She turned from the ocean to gaze at green-crusted Mauna Kea, which was wreathed in ao pua’a at its top, over 13,000 feet above her. The mist clung in defiance of what had been a warm day, and the singing blue sky was deepening into evening.

The breathtaking splendor was merely an average afternoon for the Kona coast. Tomorrow would be just like it. Yesterday probably had been.

Anake Lani hadn’t seen yesterday’s sun, nor the one before. Aunt Lani was gone. She wasn’t even Bree’s real aunt, and so couldn’t join the ranks of Bree’s ancestors. If Aunt Lani’s voice could have joined them she might almost welcome their words, but she suspected she’d gone so far from them that even Aunt Lani could not have brought her back.

The cooling evening breeze swept over her again, briefly lifting her short black hair from her neck. There was music from the car, but it fell to such low tones she wasn’t able to identify the piece. A small mercy, one she could barely appreciate.

She could sit here, just like this, for a week. She knew she was expected, but now that she was here, she did not know if she was strong enough to drive to Aunt Lani’s house and not find her there.

There is nothing you can’t do, Bree, Aunt Lani said, from the past.

Perhaps it had been true then, but it was a lie now. There was so much she could no longer do. Her left hand twitched and she recognized the urge. A crystal theme rose over the rumble of a launch leaving the marina, a line from the Goldberg Variations. It set off the recording in her head where every sterling note vibrated. Her left index finger twitched–it remembered. She tried to coil her hand as if it caressed the neck of her instrument, but it didn’t obey her.

In paradise, standing on the shore of the fire and ocean that had made the land, she’d hoped for more healing than this.

More music from the far away radio flooded her with memories of concert halls and endless airplane flights, theaters and practice rooms, rolling back in time. The past had lost none of its sharpness. The memory of the violin Aunt Lani had found for her and the music she had wrung from it was as clear in her mind as the passionate, soul-burning Bach that had soared from the Stradivarius. The music of a child was as vibrantly painful as all of the music that she would never play again.

* * *

“I suppose you’re Sabrina.” The other girl shrugged her hair over one shoulder.

Bree held out her hand.

Hands remained firmly on slender hips, then all Bree saw was a swish of long black hair disappearing into the house.

“Jorie, you can find a kind word.” Her new aunt bustled up, carrying the largest of Bree’s suitcases.

Bree was deeply aware of Jorie’s flounce into the kitchen. When she saw the small bedroom with the new twin bed installed on the far side she understood.

She had nothing of value, so unpacking took little time. Just clothes, unimportant things. She’d never need the socks, it was warm and sticky. Moist air would warp strings anyway. Just as well.

It took her only the rest of the afternoon to like Laniakilani Elenola Pukui as much as she could like any grownup stranger. Aunt Lani sang while she did everything. Funny songs about grass shacks and crab bakes, and others in Hawaiian that sounded like poetry, though Aunt Lani said they were mostly about grass shacks and crab bakes. Some were about living close to their ancestors. Aunt Lani said she would explain about that later, when Bree had had a chance to meet a few of her own.

Jorie, Marjorie Kelekia Pukui, was another matter, but Bree was used to hostility. Dee had been hostile. The last of her father’s three wives, Dee hadn’t liked Bree–the product of marriage two–at all.

Bree tried not to think about Dee. Daddy had thought it funny that their names rhymed. If there was a word for how she felt about Dee, she didn’t know it. She couldn’t play it. So she didn’t feel it. She held it in. Los Angeles was far away and the things she hadn’t been able to bring with her seemed like they belonged in Australia. She’d been having a long, no good day for months.

“You’ll be glad it’s summer.” Aunt Lani handed her a heaping plate of white fish stewed in tomatoes and pineapple. “Jorie and you can get to know each other.”

Jorie had no enthusiasm for it, and after dinner ran out to play with her friends. Bree trailed after her, pretending to study the lush green leaves and vibrant blooming flowers that carpeted Aunt Lani’s front yard. They reminded her of Schumann.

“Ignore her,” Jorie ordered from halfway up the odd tree that sent roots down from limbs to forms dozens of new trunks. “She’s only six and she’s not even related to me.”

Bree might have told them it was her seventh birthday, but she didn’t. She couldn’t play it, so what was the point?

She came in after dark when Aunt Lani called, had a bath, was read to and tucked into her new bed. The sheets smelled like the ocean that she could hear from what seemed a long way off.

“Welcome to your ‘ohana,” Aunt Lani said, after she kissed Bree’s forehead. “You will feel better soon.”

Feeling better wasn’t something she had any strength for. The days limped by. Jorie hated her. None of the kids had any use for her. She didn’t talk much, to begin with, and they all chattered so freely. They all knew Hawaiian and lapsed into it when she was around. She didn’t know what hupo haole meant, but it couldn’t be a compliment. They would gather on the fallen log at the top of the hill and tell stories, using their hands as they spoke of Pele and Kamehameha and Captain Cook. Bree watched from a distance, waiting for when Momi would sing. It was something.

Aunt Lani was nicer than Dee ever had been, Bree appreciated that. Sometimes, if she didn’t look right at her, Bree could almost imagine Aunt Lani was her mother. She moved like mommy had, quick and light.

“Do you think you could cut up the oranges?” Aunt Lani gestured at the peeled fruit and the paring knife that lay next to them.

Bree nodded, but hesitated. She wasn’t allowed to use knives. Mr. Proctor, her old music teacher, had told her never to touch one. Never.

“Go on. There is nothing you can’t do, Bree.”

She swallowed hard and didn’t know what to do.

Aunt Lani glanced at her as she stirred together macaroni salad. “What are you thinking, keiki?”

Bree picked up the knife in her right hand, holding the handle between her fingertips and thumb.

“That’s not how you hold it, to begin with. Let me show you how.”

Aunt Lani wrapped her fist around the handle. Not like a bow, then. “The trick is to keep your other hand away from the tip of the knife while you slice. I just need chunks, like that.”

The job was quickly done. Bree washed her hands while Aunt Lani went back to the macaroni salad. Bree liked the macaroni salad Aunt Lani made. Jorie was out playing, but Bree really didn’t mind helping. Sometimes Aunt Lani sang and when she wasn’t singing she had the radio playing whatever the small local station felt like that day.

“Only two more gallons to go.” Aunt Lani scooped finished salad into an old plastic tub. The tub threatened to skitter off the counter, so Bree held it in place. “I like a good party, but I don’t know what I was thinking when I said I’d bring the salad. I had planned to spend the afternoon finishing the last of that commission.”

Some noodles missed and Bree quickly scooped them off the counter with her finger and popped them into her mouth. She liked the artwork that Aunt Lani did, made up of pottery and her own knitted pieces, stained and soaked and spattered with colors. They sang when they were done, in a way.

“You have to wash your hands again if you want to help.” After Bree finished at the sink Aunt Lani observed, “That didn’t take nearly long enough.”

Bree turned her hands back and front to show she had gotten them clean. She’d even used soap.

“Whatever happened to your fingers, keiki?” Aunt Lani took Bree’s hands in her own, then looked hard at the calluses on Bree’s left fingertips. “How did you get these marks?”

She shrugged. They were going away, slowly.

“Hmm. I remember your father writing you had music lessons in that last Christmas card–too young if you ask me. Your fingers might never be the same.”

Bree pulled her hands away. Mr. Proctor had said she would never want her fingers to go back the way they had been. Aunt Lani was looking at her very seriously. Bree wondered what she was supposed to say.

Aunt Lani turned to the bubbling pot of macaroni. “If you decide to say something let me know so I can pay attention. I wouldn’t want to miss it.”

Bree wondered if she was being teased. Grownups liked to do that. Dee had always said she was teasing when she said something that hurt. Aunt Lani didn’t hurt, she just didn’t understand.

Bree went out to the garage to get another jug of mayonnaise. When she came back Aunt Lani had turned on the radio.

Neither an island ballad nor a mainland hit, she knew the music right away: Symphony Number Four in B-flat Major, Opus 60 by Ludwig von Beethoven as conducted by Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. It had been one of daddy’s birthday presents to her last year. Because of the tempo, she could tell the Bernstein from the others she had in her collection. Her records had been too heavy to bring with her. Aunt Lani didn’t own a phonograph anyway.

After a minute, Aunt Lani took the jug out of her hand and Bree put her arms around the radio. She listened.

* * *

“…Musette for Strings, opus fifty-eight. Next we’ll turn to an unaccompanied transcription of the Adagio by Samuel Barber…”

Grace, from the fates or the gods, from anywhere–all Bree wanted was grace and mercy. She didn’t deserve it, she reminded herself. Maybe, once, long ago, she’d been touched by it, but not since…not since San Francisco. Stumbling, she made her way to the car, slapping at the radio before the Adagio cut her soul to ribbons. There was a second of silence, but before she could relax, relentless memory surged again.

* * *

“I don’t get to go?” Jorie snapped her mouth shut, then opened it again. “But mom!”

“I thought you would like a sleepover at Momi’s instead.”

“But I like music. Too.” Her gaze flickered to Bree.

“Since when have you liked any music besides those Beatles?” Aunt Lani pulled her muumuu over her head. Bree loved the elegant stitching around the collar that Aunt Lani had done herself. Aunt Lani looked like a princess in it.

She glanced down at her own striped pants. She knew what hupo haole meant now, and the Los Angeles-bought pants did make her look like a stupid mainlander, a foolish white girl, even though her skin was only a little lighter than Jorie’s.

“She’s just a kid. I like it more.”

“Bree is older than both of us when it comes to music.”

“Mom!” Jorie gave the word five beats. “She’s not even ‘ohana.”

“Marjorie! You will never say that again!”

Bree stepped back. She’d never heard Aunt Lani raise her voice before. It was her fault. Now Jorie would hate her for always.

“You know what I mean.” Jorie stared at her feet.

“Yes, I do. Be glad I’m still going to let you go to Momi’s after that remark.”

“Okay.”

Bree decided it was a good time to go to the bathroom. She managed not to get in Jorie’s way until Jorie had clambered out of the car at Momi’s, a duffel bag over one shoulder.

Aunt Lani’s station wagon was hot, though the sun was near setting. “It’s not going to have any classical music, Bree. I don’t want you to be disappointed. But your mother was my dearest friend in life, and she loved her island music heritage, so I think you will like it, too. After her parents and granny died, music was all she had. It was her granny who taught her to sing.”

Bree had heard all this before, except the part about her grandmother. She didn’t know anything about her mother’s family. Her father hadn’t wanted to talk about it, and she could even now only barely remember her mother. She could remember her mother’s laugh. She remembered playing a game where mommy wrapped her long, beautiful hair around Bree’s waist while Bree yelled, “Rapunzel, let down your hair!”

And the song about the turtles, she’d never forget that. She didn’t forget music.

Aunt Lani was quiet for a while, and Bree hummed the gentle lullaby. Honu, grandmother of the waves, your shell like a star in the sea, flying honu take me away, to where my true love will always be.

She still missed mommy and she couldn’t even think about daddy without feeling like she’d cry. The night mommy went away in the ambulance Bree had sung it to herself. She’d kept on singing it to herself every night since mommy couldn’t anymore. Dee hadn’t liked it, though, so she’d stopped doing it so anyone else could hear.

After daddy’s funeral no one could decide where Bree would live. Tbe documents said who got daddy’s money, and her half-brother, apparently, got most of it. Sean was twenty-five and didn’t need a baby around, especially one with a noisy violin. She’d heard him and Dee talking about her. She didn’t know what a caterwaul was but it couldn’t be a compliment, no more than hupo haole was. Bree had something called a trust and trustees and Dee really hated them because there wasn’t a sum lump or something like that.

She didn’t understand things like antibiotic and embolus, but she’d learned to spell them. Infection took mommy and embolus took daddy. People called them surprises, but not the kind like a birthday party. She’d played songs that made her feel better because she was so alone, but Dee hadn’t like the music as much after daddy died. There hadn’t been any music after awhile. Not until Aunt Lani had turned on her radio.

“We’ll sit on the ground, too. I brought blankets. It’ll be so pleasant near the water. As long as you’re not expecting an orchestra.”

Bree shook her head. She was not expecting anything like when daddy had taken her along on a business trip last year just so she could hear the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Dee had hated that she had gotten to go. But she would never forget her first vision of the hall–the soaring ceiling, the rows and rows and rows of seats, the balconies, the stage filled with music stands and waiting instruments. She had held her breath as much as she could. Aunt Lani had told her the island of Hawaii did not have a concert hall even half that size.

“The heiau is a sacred place, so just watch what I do and you will learn. I don’t think there will be any other children, but you never know. We won’t be inside the real temple, but between it and the beach. I hope you like it.”

Bree didn’t care about the details. It was music and performed live. She would hear instruments singing. The radio was good, but it wasn’t the same.

She held tight to Aunt Lani’s hand and then snuggled close after the blanket was spread out. There wasn’t a real stage, but a cleared area with a rough awning over it. The drums and microphone said that was where she should keep looking for the music to start. There was a small guitar resting on a stand there, its strings covered just below the tuning keys by a steel bar. She wondered what that would sound like. Portamento, perhaps? Would it give the guitar legato, like a trombone?

She noticed the man as soon as she settled into place. He was enormous. His legs were like the banyan tree in Aunt Lani’s yard. He was so large he might have been two trees in one. His laugh carried as he talked. At no particular point in time that she could see he heaved himself to his feet, without stopping his conversation, and went to the microphone. Then she saw that he was carrying a four-string guitar, very small. It looked so tiny against his huge chest it might have been a necklace. Aunt Lani had explained about ukuleles, so that was probably what it was.

He spoke for a time about the heiau and the plight of the native Hawaiians, caught between the bitter loss of community in the past and the unavoidable, modern future, a tiny cluster of gods-made islands in the shadows of superpowers. All the while his fingers strummed the ukulele softly, making it sing so sweetly that Bree found her mother’s song rising in her too, and she wanted to sing with him, because maybe he would know about the silence inside her. When he spoke in Hawaiian she almost felt she could understand because the ukulele translated the words.

The concert was long and mostly in Hawaiian. Sometimes the music was so low that the sound of the ocean behind them became part of it. Other parts were loud enough to send sea birds cawing overhead. The moon rose and the walls of stacked rock that framed the heiau gleamed in the silver light. Her shoulder blades itched all at once and something whispered to her. It was so gentle that the silence almost covered it up. Milimili keiki…it could have been the waves rustling onto the sand.

When it was over Aunt Lani took Bree by the hand and led her toward the awning. They waited for a long time, but finally the singer, looming like a giant–Bree wasn’t afraid–noticed them.

He greeted Aunt Lani by name, with a kiss on her cheek, and they spoke of family. Bree only saw the ukulele resting on the stool near the microphone.

“This is the newest member of my ‘ohana,” Aunt Lani said. “She’s Ienipa’s child and came to me because her father passed on in the spring. He had no family and her…guardians thought Sabrina belonged with Ienipa’s people.”

“And you’re all Ienipa had.” The singer smiled down at Bree, then his smile faded. He gave her a long, piercing look. Bree thought about words she might say, that he might understand. But before she could find them he nodded. “Go ahead.”

He did not call her keiki.

She left Aunt Lani’s side to pick up the ukulele. She heard someone say something sharp to her, but the giant, the one who gave her such a moment, shushed the protest.

She could not hold it the way he did–her hands didn’t know his way. Instead, she tucked it under her chin and plucked the strings with her right hand. She heard the notes, then let her left hand curl around the neck so her fingers could press down on the strings. She closed her eyes. Pizzicato would work with this instrument, but none of the melodies she knew fit strings so strangely tuned.

She remembered his sad song of the warrior’s lost bride, and she picked it out to learn the way of the ukulele.

Her voice…she could feel her voice coming out, even with this strange instrument. She learned the resonance of the strings and their response to the pressure of her fingertips. Middle C was here on a violin, but there on a ukulele. Her fingers would remember now. The ukulele wanted to sing. The melodies she knew began to flow.

At some point she was aware that a large, infinitely gentle hand was resting on the top of her head as she played.

* * *

“You don’t have to come with us, Jorie. We’re just driving into town for a bit.”

Bree was surprised when Jorie got in the front seat next to her. It was the last day of summer and Jorie’s friends probably had plans. “I got nothing better to do.”

Aunt Lani’s big station wagon chugged into Kona proper, squeaking to a stop near the farmer’s market.

“Ah, mom, are we just getting vegetables?” Jorie slumped in the seat.

“Not just that. You staying or coming?”

Bree liked Jorie’s sandals. She thought it would be nice to be eight, to have long legs and hair that seemed to float even when there was no breeze. She followed Aunt Lani into a store. The smell–the sharp mix of musty paper, mineral oil and resin–took her breath away.

She stood staring while Aunt Lani talked to the man behind the counter.

“I can’t afford a really good one,” Aunt Lani was saying. “She’s had some lessons and seems awfully good for a child.”

Their voices faded to a rustling background. Bree could only see that behind the man, in a locked case, were violins. From a factory, but that didn’t matter. Violins.

He was holding one out. Holding it out to her.

“Do you know how to tune it, little sister? I can do…”

“Her father told me she liked music…”

Her fingers sounded the strings and turned the tuning keys. She tightened the bow.

“…Advise you to keep it cheap right off, because kids change their minds…”

Bow met strings, brushing notes into the air.

“…This is so boring…”

She closed her eyes and found her voice in the violin.

Vivaldi seized her. She’d been working on the piece when her father had died. Winter, sawing, piercing, swirling cold of ice and snow, jabbing pain and exultation, fierce spirals of tone and rhythm…Vivaldi, goodbye, grieving. Vivaldi…Dee hated Vivaldi.

She opened her eyes when she finished. Aunt Lani looked as if she might cry. The man behind the counter was sitting down, his mouth slack. Jorie blinked at her.

“I had lessons three times a week and on Thursdays Mr. Proctor said I couldn’t practice, I had to let it alone for the whole day.” Bree ran out of breath. “I like Vivaldi and Mozart. Mr. Proctor said that I should leave Bach out for now, but I practiced it on the sly because Dad liked the Goldbergs and I could do the opening to the first one even though it takes a bigger hand to make some of the combinations and my arm gets tired of bowing on the longer pieces and my calluses will come back I suppose and I should start doing the exercises for my arms and shoulders again…”

* * *

Bree shook herself out of the past, away from the day when she had reclaimed her voice. Aunt Lani had had only instinct to go on, but she’d known Bree wasn’t complete. She cared enough for her best friend’s daughter that she’d found what was missing.

The violin on the passenger seat called to her from its case. It cost infinitely more than the one Aunt Lani had bought on credit that day, but it was still only practice quality. The beautiful, luminous Guarneri was in the care of her agent, and another more expensive still was in a secured, insured, climate-controlled storage vault. Not that she would ever touch either of them again. She could hardly bear to subject this less powerful instrument to her clumsy fumblings. Like the others, it wanted to sing, but she could no longer help.

Share the Book Love:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Threads (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Bluesky (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- More